Long before California’s farm-to-table movement and Alice Waters, there was Korean temple food: a cuisine that dates back thousands upon thousands of years with veganism at the foundation for religious reasons.

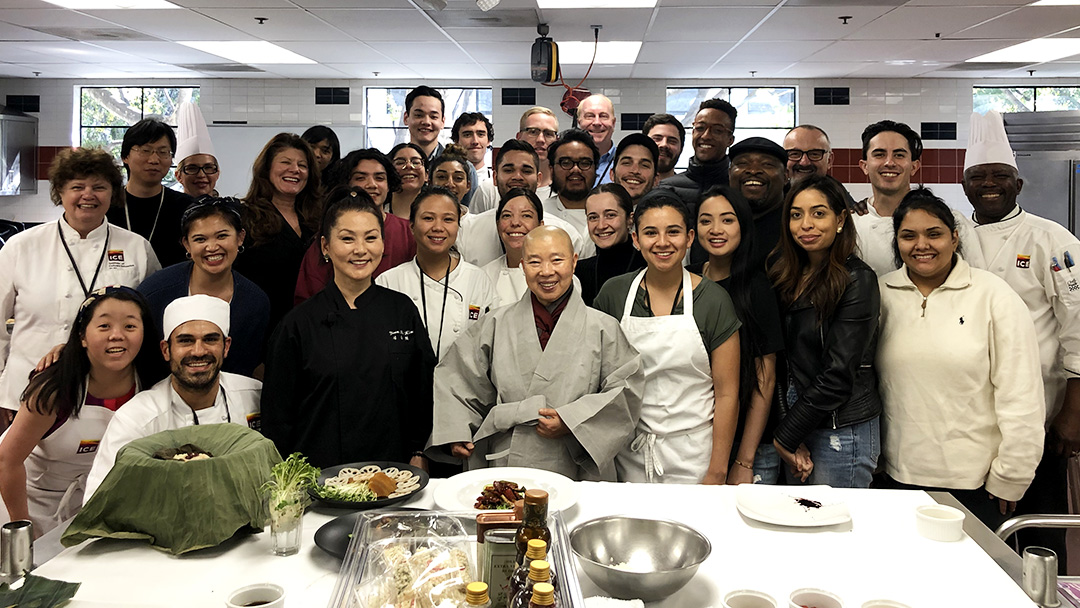

Through ICE alum Yoon Hee Kim’s (Culinary, ’05) translation, students at ICE’s LA campus learned about Jeong Kwan’s philosophies and daily life, wandering and tending to her garden at the Baegyansa temple where she cooks for herself and two other nuns, as featured on Netflix's "Chef's Table."

“What am I relying on to connect the past, the present and the future?” she asked. “Consider all of the universe that’s around us. Within that nature, the totality of the universe, you have the wind, the sunshine, the rain and all that surrounds us to circulate energy.” Jeong Kwan discussed the difference between plants, human beings and four-legged animals that have free will to get up and move and create action. Plants do not, but as Jeong Kwan emphasized, we’re all living beings.

She focused on mindful cooking — though her cuisine is vegan, Jeong Kwan did not preach against consuming animal products. Instead, she endorses overall respect for ingredients. “We are taking what was once living for our own consumption. We have cut the lives of the plant ingredients, so it’s our responsibility to not only know its essence, but to understand its energy form and to respect it.”

Dressed in her signature, pristine gray robe, Jeong Kwan taught the students how to prepare lotus-wrapped rice with three beans. She pre-soaked and steamed rice, then removed the core of the lotus leaves in advance. Students placed the leaves on cutting boards, dark side up, then tightly wrapped a fistful of the steamed rice, a slice of lotus root and three beans in the leaves, before steaming again for about 20 minutes.

Jeong Kwan demonstrated braising shiitake mushrooms with soy sauce and water and prepared a dried persimmon and cucumber salad. She brought syrups, sauces and a soybean paste, which she made from plants at the hermitage, for the demo. Yoon Hee explained that the paste was soaked, cooked and fermented. Jeong Kwan’s soy sauce was aged for five years in earthen jars where it was left to develop in the sun and wind. What then might have been overlooked as a simple salad of cucumbers actually took years of work. Jeong Kwan's vinegar of persimmons was aged for four years, and she used a syrup made from plums.

“It is quite possible that in time these ingredients could be me, and I could become these ingredients,” Jeong Kwan explained. “And thus we are, in fact, one.”

Her jars are where she lets “nature do its thing.” She explained that air, rest and nature form a natural acidity for the fermentation process to occur. “It’s all on its own,” Jeong Kwan explained. “Human beings have nothing to do with it.” Year after year she makes her persimmon vinegar, and year after year, its taste varies due to climate change.

“Everyone here should be respectful of the ingredients, to be able to cook with love, share with one another and create something that at first makes the self happy and then share that joy when you go to serve it,” she advised students. “We can all do that as we continue in our journeys as chefs, as people who create food for others. It is not just about serving others, but about creating a humanity that is filled with peace, happiness and joy.”

Pursue a career that brings you happiness at ICE's Los Angeles campus.