Michael Lomonaco’s Steak and Seasoned Career Advice

The legendary New York City chef spoke to ICE students and alumni at a virtual event while preparing a hanger steak at home.

Michael Lomonaco is the executive chef and co-owner of two New York City restaurants, Porter House Bar and Grill and Hudson Yards Grill.

A native New Yorker with Brooklyn roots, he grew up in a household where cooking and vegetable gardening were some of his parents’ passions. In his teens and 20s, Michael’s passions were artistic, but not culinary arts. First it was photography and that led to acting on stage and screen till age 27.

He studied culinary arts at Brooklyn Technical College and got an incredible post-graduate education at Le Cirque, working under acclaimed chefs Alain Sailhac and Daniel Boulud. Chef Michael, like other chefs of his generation, became proficient in the style of New American cooking, and he eventually became the executive chef at the famed 21 Club.

In 1997, that led to his assignment as executive chef and director of Windows on the World, on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower in downtown Manhattan. He turned it into one of the highest grossing restaurants in America, three years in a row, but as some of you know, it’s the most famous restaurant that was destroyed in the 9/11 attack. Chef Michael only survived because he was in the building’s lobby getting his glasses fixed when the first plane hit.

Fast forward to 2006, when Chef Michael became the executive chef and owner of Porter House in the Time Warner Center. That year, Esquire named it one of America’s best new restaurants, and it has developed a reputation of excellence. In 2017, Grub Street declared it the "absolute best steakhouse" in New York.

In 2020, Chef Michael introduced Hudson Yards Grill at the monstrous mall of the same name. Forbes called it a “perfect American brasserie” with “something for everyone,” and the New York Post said the burger would put the new mega-complex “on the map.” Along the way, Chef Michael has combined his talent for acting with his culinary skills. He hosted a show called “Michael’s Place” for three years on the Food Network and “Epicurious” for the Travel Channel. He has also appeared on TV with Julia Child, Anthony Bourdain and David Letterman as well as on the “Today” show and “The Chew.”

I have known Michael for more than 20 years, enjoyed his friendship, and admired his style and spirit. So, it was a pleasure to interview him via Zoom for ICE students and alumni. I used our talk as a chance for me and others to learn more about the world of beef and steakhouses.

Aging Beef

I asked him about the difference between dry aging and wet aging. He explained that for beef, dry aging takes place in a controlled, refrigerated, humid environment at temperatures around 34-38 F. With wet aging, the piece of beef is placed in a Cryovac bag and stored at similar temperatures. With dry aging, flavor is enhanced because (1) moisture evaporates, which concentrates the remaining flavor, and (2) enzymatic aging. Enzymes break down the meat’s connective tissue, which results in a more tender product. But one of the issues with dry aging is that a given piece of meat can lose up to 20-30% of its weight. So for the chef who bought the meat at a certain price per pound, there is an economic consideration to letting your prize protein evaporate and shrink.

I learned there are variations in how long chefs and restaurants will dry age beef. With dry aging, Chef Michael targets 28 days. He pointed out that the famed French chef Alain Ducasse ages beef for only 21 days. After a certain amount of time, like 60 or 70 days, the piece of beef will develop a certain “funk” aroma that is too strong for most people. But some customers like it, and for a steakhouse, having steak dry aged for over 50 days is sometimes the basis for a nightly special. Porter House sources USDA prime from Pat LaFrieda Meat Purveyors, which ages steak for 21 to 60 days.

Kobe Beef vs Wagyu

Another topic was the difference between Kobe beef and wagyu beef. The basic answer is simple: Kobe is a place (a city) in Japan, and wagyu is a breed of cattle (bred near Kobe). Notably, the translation of the word wagyu is “Japanese cow.”

On Eat This, Not That, Sodexo Executive Chef Todd Brazile says that wagyu beef quality is evaluated in four categories: brightness and color, firmness and texture, marbling and quality of fat. “You can expect wagyu beef to be more tender and juicier than standard beef, with a nice buttery flavor. Quality wagyu has marbling, the streaks of fat that run throughout beef, within the muscle and not just around the outer edges.” he says.

The highest quality Japanese wagyu beef is very expensive: At auction, cows can sell for as much as $30,000 versus a typical American cow, which sells for around $1,500. There is an “American-style” wagyu that is a crossbreed between American angus and Japanese wagyu. Chef Michael has both options on his menu at Porter House, and he pointed out that because the Japanese wagyu is a “very rich (and expensive) dish,” it’s not uncommon for several guests to share a 12-ounce wagyu portion as part of the meal.

Prime Beef

Of course, in America, higher quality beef usually falls in the USDA category of prime beef. A cut of beef is considered prime when the cows have several months of grass feeding after being grain-fed, and a certain level of marbling is achieved. Only 2-3% of all the beef in America is graded as prime. Chef Michael points out that the prime beef he sources at his restaurants is antibiotic-free and hormone-free.

Hanger Steak

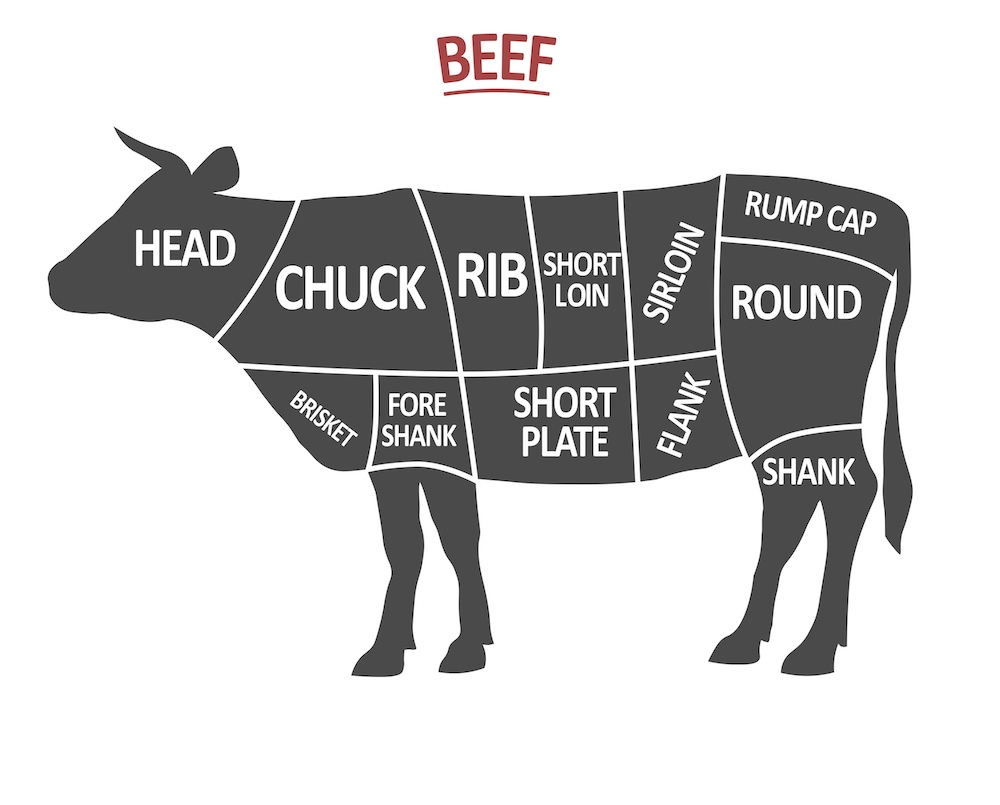

Michael was at home for our conversation, cooking a hanger steak to demonstrate an example of a delicious and less common cut. Anatomically, the hanger steak comes from the short plate on the underside of a cow. Each cow only has one hanger steak so it has never been easy or likely to have the cut merchandised in a butcher shop or supermarket. In fact, the hanger steak is also known as the butcher’s cut because traditionally it was a leftover cut of the cow that the butcher would have a hard time selling.

Study cuts of beef and butchery in Culinary Arts.

Learn as Much as You Earn

“I loved food and cooking, but I had no professional experience,” Chef Michael reflected on his career change from acting to becoming a chef 34 years ago. “I got myself an education. That education in culinary arts and hospitality put me on the right path.”

He advised culinary students on externships and moving on through restaurants. “You choose the job as much as the job chooses you. You give them everything you have everyday so that you can learn and maximize the experience for yourself,” Chef Michael explained. “It’s important to commit yourself to a restaurant. I don’t think you should move until you’ve learned everything that restaurant has to teach you.”

As you develop, Chef Michael advises, “Cooking is a discipline. It starts as a skill, it turns into artisanship (you become an artisan at it), and then at some point you can break through and become a skilled and talented creator of food. You never stop learning. To this day, I challenge myself at work in cooking and in management.”

One of Chef Michael’s interesting points of view is that writing a menu is akin to writing a movie script. He said in a script, the writer introduces characters, and while each one of them is different, it’s important that they interrelate well and collectively make a good story (or cast). In the same way, the different sections of a great menu should interrelate well and collectively enable a great meal.

True or False

I knew from earlier conversations that Chef Michael has cooked for a range of celebrities, including athletes, musicians and politicians. When I asked if it is true that he cooked dinner (at separate occasions) for Bruce Springsteen, The Who, and Crosby, Stills & Nash, he answered yes. But he would not offer up any stories or anecdotes from those nights saying instead that “he treats all customers like VIPs,” and that in his mind, the biggest VIPs were “the ones who come to your restaurant regularly, like once a month or more.”

Reopening Outlook

At present, both of Michael’s New York City restaurants remain closed due to the pandemic. Being inside large, mixed-use complexes like Time Warner and Hudson Yards prevents outdoor dining, takeout and delivery, but Chef Michael is targeting early November to reopen both restaurants. At that point, hopefully, New York City will have increased the allowable seating capacity from 25% to 50%, and at that level, opening could be economically viable. As Chef Michael related, he is looking forward to once again cooking with his teams and practicing the art of culinary hospitality that he so enjoys.

Pursue an art you enjoy with ICE's career training programs.

Add new comment