I was recently invited to attend the third annual meeting—or summit—of the Basque Culinary Center held at Blue Hill Stone Barns in Tarrytown, New York.

The center is charged with furthering innovation in the field of culinary arts and, given the high profile of the chefs involved, (notably, board president Ferran Adria, among others), their activities have taken on issues and research of greater scope. Esteemed with the moniker ‘G9’, the board members present at this year’s summit included Michel Bras, Joan Roca, Yukio Hattori, Alex Atala, Gaston Acurio, and Enrique Olvera, as well as host chef Dan Barber.

The theme for the gathering was ‘Seeds: Cultivating the Future of Flavor’, addressing the idea of designing plants for flavor and the work of plant breeders (an important, but seldom seen link in the farm-to-table food chain). Other attendees included fifty chefs, food writers and policy-makers, as well as the nation's leading growers and breeders of grains, fruits, and vegetables. The purpose was to broaden our farm-to-table perspective and to discuss issues that may greatly influence the work of chefs in the future.

The day began with short presentations from two renowned plant breeders with slightly different approaches. Michael Mazourek of Cornell University studies plant genetics to better understand and isolate the mechanics of how plants work. Conversely, Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed takes a more hands-off approach, testing small plots of plant varieties and selecting the individual seedlings with desired attributes to further refine and produce future seeds. It’s important to note a distinction between the work of these small breeders and large-scale commercial farms. Both forms of selective breeding are not "genetic modification" we hear happening in agribusiness (see: GMOs), but rather a reaction against it, representing the ongoing evolution of plant varieties that have been developed over thousands of years.

When it comes to the use of heirloom ingredients, few chefs have been more praised than Chef Sean Brock, of McCrady’s and Husk in Charleston South Carolina. He spoke on their role in Southern food traditions along with Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills, while Alex Atala presented details on his work preserving and promoting indigenous Amazonian products, such as rice, honey, and vanilla.

Of particular interest to me was the brief talk given by Stephen Jones of the The Bread Lab at Washington State University’s Mount Vernon Research Center. Jones is one of very few scientists looking at a wider array of wheat strains that lie outside of those varieties grown for commercial use. For example, the number of species of wheat that go into industrial flour number less than ten, while Jones has examined tens of thousands. At any given time, hundreds of individual strains are growing on his team's test plots in the Washington’s Skagit Valley north of Seattle.

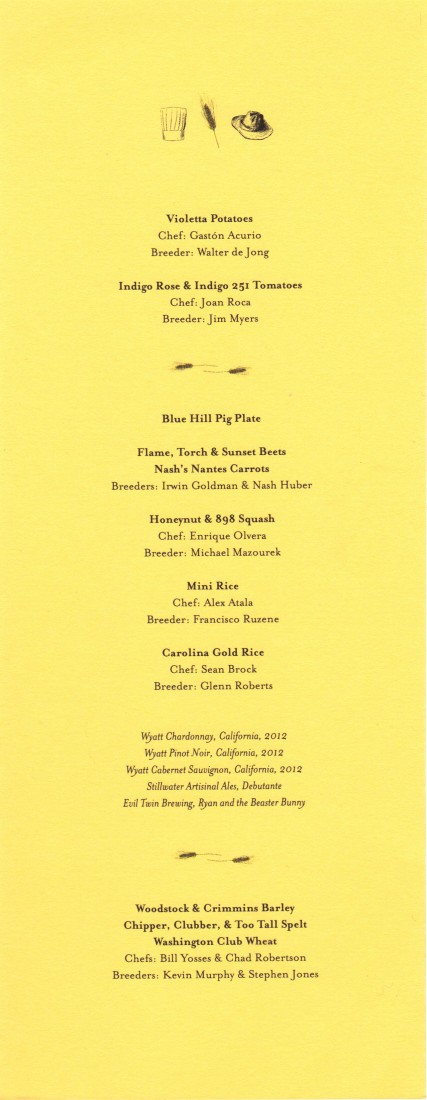

The inspiring and informative day concluded with a thematic multi-course dinner, pairing guest chefs with breeders to create dishes that featured the unique properties of experimental plants.

While events such as these present an opportunity to catch up with old friends and colleagues, they also offer a chance to network with a wide variety of new friends and food professionals. This session set the stage for a whole new perspective, a continued exchange of ideas about the complex possibilities contained in each seed.

Of great interest to me was the sentiment expressed by Ferran Adria, who repeatedly stressed the importance of teaching and sharing this knowledge with the next generation of chefs—today’s culinary students. As we become more informed about our local and international food systems, a deeper understanding of and respect for our ingredients has proved just as important as the techniques we apply to them.