In my last blog post, I described my search for historical traces of chocolate in lower Manhattan. In a relatively short time, chocolate traveled from its South and Central American origins to Europe and later into North American settlements. Though the early Dutch colony of New Amsterdam rose and fell well before chocolate became a permanent fixture, by the early 1700s, New York’s port was an important link in cocoa trade.

Among those merchant families importing beans, the first glimpse of cocoa processing can be found on the island. By the end of the American Revolution and the turn of the 19th century, the city grew northward and chocolate had gained popularity, with several chocolate makers setting up shop.

One might think that researching this topic is as easy as entering “New York,” “chocolate,” and “history” into a search engine. Surprisingly, those yield scant results and even less clues to work with. A few books pointed me in the right direction—some names and places—but I soon realized I was drifting into relatively uncharted territory.

I eventually found that the best way to crack the cases of these mysterious chocoate-makers was to begin with surviving city directories whose listings often provide a name, an address and most importantly, an occupation. The first of these directories in New York was published in 1786, with increasing regularity in years to follow. From there, genealogy records, newspapers, civil documents and maps added more life to the stories.

Most often, the labyrinth comes to an abrupt halt; I may come across a name and an address, but all other details remain a casualty of history. It is worth noting that chocolate was still consumed as a beverage in these early days, though with the chocolate-makers of the 1800s, we witness a slow and steady shift toward the refined bars of eating chocolate we would recognize today.

Most often, the labyrinth comes to an abrupt halt; I may come across a name and an address, but all other details remain a casualty of history. It is worth noting that chocolate was still consumed as a beverage in these early days, though with the chocolate-makers of the 1800s, we witness a slow and steady shift toward the refined bars of eating chocolate we would recognize today.

Unclear is the extent to which chocolate may have been processed by these craft producers of their day, but certainly roasting, winnowing and grinding of cocoa beans was essential, no matter the final product.

Chocolate was often manufactured alongside other milled products. In 1815, Samuel Holcombe was listed at 47 Gold Street, as a manufacturer of both chocolate and mustard. Over at 227 William Street, Charles Cogswell was also multi-tasking in mustard and chocolate as late as 1825, though it appears his son Jonathan stuck to mustard as he moved the business uptown to Spring Street a decade later.

Many grocers and retailers most likely processed small quantities too, like Abraham Wagg or Frederic Shonnard at 220 Bowery. According to the 1791 directory, Peter Montayne at 182 Queen Street coupled chocolate making with the seemingly disparate occupation of blacksmith.

As the number of independent chocolate-makers grew, one would imagine that, with competition and branding, the quality, quantity and variety of products would increase as well. From the period after the American Revolution (during which cocoa trade into New York was limited) through the first half of the 19th century, I discovered dozens of names and places associated with chocolate in Manhattan. Many of these chocolate-makers appear and then disappear from records within a few years, but we clearly see chocolate activity spread throughout the growing city.

Among those uncovered, but with little of their story to tell, include:

- John Austin, listed as a city resident and chocolate-maker in 1787 court records

- David Whitehill, at 32 William Street in 1791

- Joseph and Joshua Leavy, at 15 Broad Street from 1786 to 1799 (later at 2 Water Street in 1801)

- Jedediah Waterman, at 322 Water Street from 1791 to 1805

- John Black, at Murray Street and Chapel Street (today West Broadway) in 1812, and later at 182 Bowery in the 1830s

- Noel Blanche, at 28 Beekman Street, from 1808 to 1819

- Peter Malard, on Barclay Street and later at 84 Duane Street from 1822 to 1827

- Silvanus Horton, at 47 Gold Street from 1822-1830 (note it is the same address for Samuel Holcombe’s mustard and chocolate business mentioned above)

The lives of these chocolate-makers offer a bit more color, context and background for further research:

- An early branch of the politically powerful Roosevelt family dabbled in chocolate. John Roosevelt (a civic leader in his own right) milled chocolate on Maiden Lane until his death in 1750, passing on the business to sons Cornelius and Oliver.

- Peter Swigard, listed as chocolate-maker but also as a tobacconist, occupied Bayard Street from the 1750s through the 1770s. It is possible Swigard learned the craft in Philadelphia before moving to New York.

- Peter Low, chocolate-maker at Maiden Lane and Broadway in the 1760s-1770s, may have also doubled as a cabinet-maker. Eventually he would move his chocolate business across the Hudson River to New Jersey. Merchant Nicholas Low, who appears to be his brother, sold Peter’s chocolate on the docks near Coenties Market. As a side note, in researching specific historical names and places, one is often confronted with a darker context of the times—a March 1771 newspaper notice announces a reward for a runaway slave in Low’s “employ.”

- Brothers Francis and John Van Dyk were part of another chocolate-making legacy. Their father Nicholas operated a chocolate mill in Newark as early as the 1760s before setting up in the city. Various addresses are listed over the years from 1786 to 1801: 48 Queen Street in 1786 (Queen Street would later be named Pearl Street and at the time would have marked the shoreline of the East River), 66 Broad Street and 28 Beekman Street (again, note the same address a decade later used by Noel Blanche).

- Tobias Van Zandt, an early political figure in the city after the Revolution, made chocolate at 92 Water Street until his death in 1794. Minutes of a city council meeting in 1796 suggest a prior professional relationship between Tobias and Jedediah Waterman (noted above), when his widow Mary leased property to Waterman.

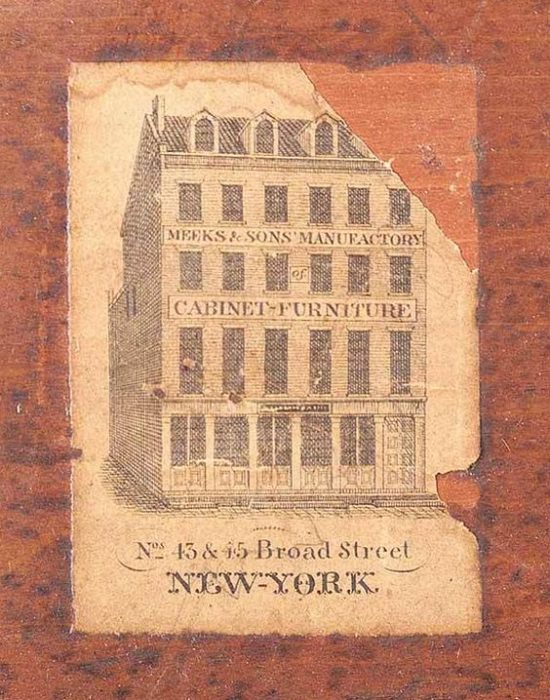

- The Van Dyk family introduced chocolate, albeit briefly, to another prominent family at the turn of the century when Joseph Meeks married John Van Dyk’s daughter Sarah. Joseph would become one of the city’s most celebrated and prolific furniture-makers, but was interestingly involved in the chocolate business in 1814 and 1815 at 45 Broad Street, the same location that would later manufacture furniture. One might assume a sluggish economy at the outset of the War of 1812 forced Meeks to give his wife’s family business a try before returning to his original calling and moving his shop up to Vesey Street. To this day, surviving Meeks pieces fetch high prices among collectors.

- French-born John Juhel didn’t make chocolate, but by many accounts was responsible for much of the cocoa bean trade coming into Manhattan in the early 1800s. Shipping records survive that detail his extensive import and export business. Juhel’s office was at the heart of what would grow into the bustling market on Washington Street, between Liberty and Cedar Streets.

- John Wait, originally from Boston, established a chocolate business first at 228 William Street by 1815 and later on Elm Street in the 1830s, near what at the time would have been referred to as the “Tombs”—New York’s notorious prison. Dominating headlines of the day, Wait’s two young sons died tragically in an 1816 steamboat accident in New York harbor.

- Perhaps the longest running chocolate-making dynasty in the city of that era was that of John Poillon and sons Peter and John Jr., whose business spanned nearly six decades. By 1808, John was listed at 116 Bowery near Grand Street. The sons moved their operation around the neighborhood over the years, up the Bowery from what we would today call the Lower East Side into the East Village near Astor Place. Though it appears Peter filed for bankruptcy in the early 1840s, an 1860 newspaper gossip column of sorts suggests that “old Peter Poillon…made a fortune making chocolate.”

- By 1827, what would evolve into the iconic Delmonico’s restaurant (perhaps the first “fine-dining” restaurant of its time) included confectionery and chocolate manufacturing at 23 William Street. Brothers John and Peter Delmonico operated the pastry shop and cafe at that location until it was destroyed by fire in 1835, a few doors up from where the latest incarnation of the restaurant still stands.

The early 1800s saw much change for the new country and its fastest growing city. At the same time, chocolate production was changing as well. The capabilities of the Industrial Revolution would transform coarse blocks of chocolate into “digestible” cocoa powder and refined bars for eating and, eventually, a staple in confections of all kinds.

Large factories and nationally-known brands would emerge out of Manhattan, flourishing into a golden age of chocolate manufacturing. Some of these chocolate-makers would survive into the 20th century before being absorbed by ever-growing companies and ultimately moved out of the congested city. My next post will look at this period, in search of any traces of chocolate manufacturers that may still remain.

Ready to study pastry arts with Chef Michael? Click here to learn more about our pastry arts program.