As we look back at the latter half of the 19th century, continuing the results of historical research I’ve posted here and here, we arrive upon what might be considered the “golden age” of chocolate manufacturing in Manhattan. We see what began as a localized industry concentrated in lower Manhattan shift from small-scale “independent” makers to the greater reach of regional and nationally known brands, whose sizable factories often took up the length of a city block, moving uptown as the city continued to grow in size and influence.

With the industrial revolution of the 1800s, chocolate and cocoa made an interesting transition from the beverage served at coffeehouses and pharmacies into the realm of confections. The innovation of pressing ground cocoa beans into its cocoa butter and powdered components (a process perfected by Dutchman Casparus Van Houten Sr. in the 1820s) allowed for a number of new applications and refinements.

We first see this shift in early advertisements extolling the virtues of “digestible” cocoa — lower in fat and thus lighter and easier to prepare. Extra cocoa butter from this pressing would soon be added to bars of “eating” chocolate, leading to the smooth refined textures of the bars we consume today.

Of course, the range of traditionally sugar-based confections expanded with the introduction of sweet chocolate products. While I tried to limit my own research to manufacturers who produced chocolate from the cocoa bean itself, those lines between chocolate-maker and confectioner began to intersect even 150 years ago — a distinction that continues to confuse most consumers today.

Indeed, many of the most prominent chocolate companies in New York City branched out into chocolate candies in addition to manufacturing plain bars and cocoa powders. I’ve come to think of the latter half of the 19th century as New York’s “golden age” of chocolate, in part because of the growth in number of chocolate makers in the city, from a handful in the early 1800s to a dozen or more before the turn of the 20th century.

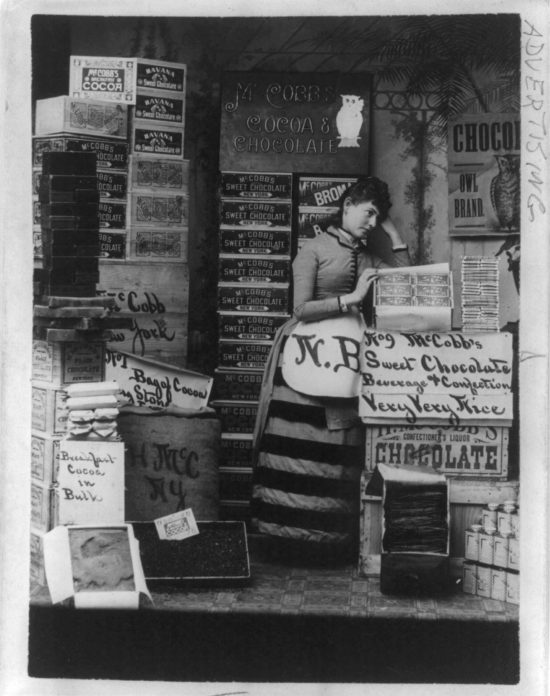

Much of what we know of chocolate culture during this period is preserved in the form of ornate tins and whimsical advertisements of the day. One might also imagine the role these chocolate makers played in the daily life of the street, tempting passersby with colorful displays, and perhaps a view of the chocolate-making process itself.

One contemporary account describes the shop run by Felix Effray at 64 East 9th Street, whose stone melangeur was prominently positioned in the store’s window:

December 10, 1849On the corner of Broadway and Ninth Street is a store kept by Felix Effray, and I love to stand at the window and watch the wheel go ‘round. It has three white stone rollers and they grind chocolate into paste all day long… (Diary of a Little Girl in Old New York, by Catherine E. Havens)

Effray was among a group of small, independent chocolate businesses in the city; we first see him at Broadway and Grand in the early 1840s, then at his shop near Astor Place, which he operated until at least 1880. Eugene Mendes, whose chocolate career spanned the same period, began on William Street and later moved to Fulton Street in lower Manhattan, then to Leonard Street in Tribeca, and finally to Broadway near Bleecker Street — one of the few chocolate-related buildings of its time that still stands, at least in part, to this day.

New York poet Walt Whitman was known to have frequented an adjacent bar during the time of Mendes’ chocolate operation. Maine-born Henry McCobb’s Owl Brand chocolate was short-lived and the site of his 1880s shop on East 22nd Street near Gramercy Park is now a modern apartment building. McCobb was among the first to use photography in his advertising.

Claude Crave made chocolate at the same location in the years after McCobb, and with him we see not only the transfer of existing chocolate companies, but also an example of shifting partnerships in New York’s chocolate “community.” Crave started making chocolate in SoHo at 16 Grand Street in the 1870s and at 176 Chambers Street in the 1880s.

Though the relationship between Crave and McCobb is unknown, Crave partnered over the years with Philander Griffing and Alfred Martin, who at various points were independent themselves. Martin was also a partner of Mendes years prior. Other similar professional relationships I’ve uncovered suggest a tight-knit community and exchange of ideas and skills that mirror the craft chocolate industry today.

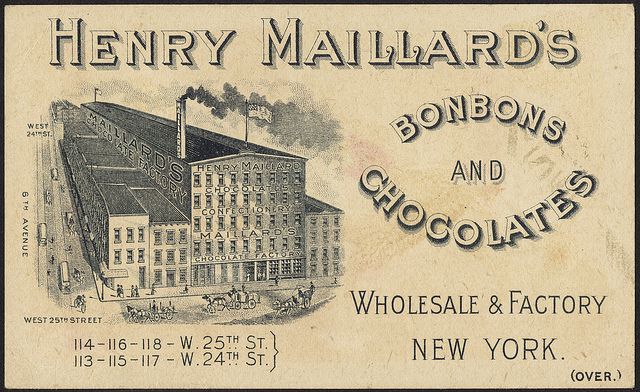

In contrast to the small independent makers, likely limited to serving the local or regional consumer, larger companies with broader reach emerged, with large factories that no doubt employed the latest in chocolate-making machinery. Henry Maillard emigrated to New York in the 1840s and built an empire that culminated in a massive factory along Sixth Avenue, as well as a flagship retail store that stood nearby at the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue across from Madison Square Park (the current site of Eataly).

Herman Runkel began making chocolate at Maiden Lane and Broadway downtown in the 1870s and eventually operated out of a block-long facility on West 30th Street near today’s Penn Station. Huyler’s was another well-known brand that continued into the early 1900s, with a modest factory at Irving Place and 18th Street that opened in the 1880s.

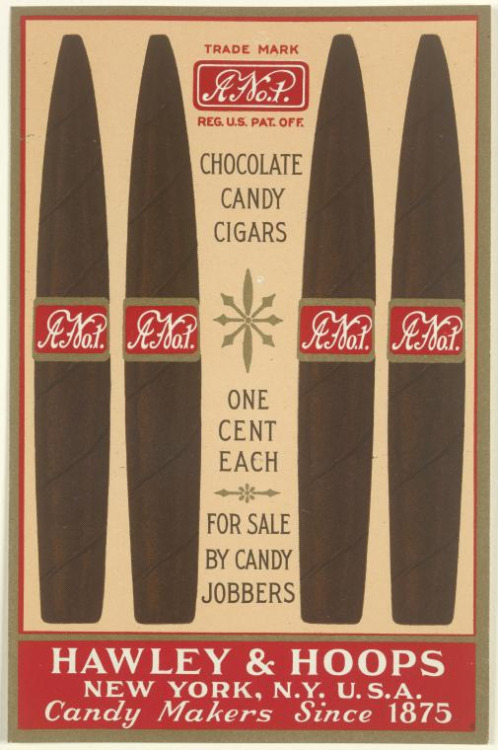

John Hawley and Herman Hoops, two independent confectioners, would join forces to create the Hawley & Hoops brand that would later be acquired by Mars; their factory on Lafayette Street just below Houston Street now houses fashionable condos. Of note is the fact that many of these companies used chocolate making equipment manufactured by Jabez Burns (a pioneer in both coffee and cocoa roasting) at his factory at 43rd Street and 11th Avenue.

Other companies, both domestic and foreign, would at various times set up shop in New York for retail and for limited manufacturing. The Massachusetts-based Walter Baker Co. was perhaps the most prominent brand of its day, with offices in lower Manhattan, and at a later date, ownership of the East 22nd Street factory previously occupied by McCobb and Crave.

English import Cadbury ran its New York operation out of 78 Reade Street in Tribeca, and Emile Menier opened an outpost of his French company nearby at Greenwich and Murray Streets.

One surprising discovery was the brief existence of a Hershey factory at 21st Street and 6th Avenue around 1920; it is a bit ironic that I began this project looking for chocolate near the current downtown location of ICE, when it existed just a block away from our former facility!

After the turn of the 20th century, virtually all of the chocolate-makers in New York faded or were simply absorbed by larger companies that eventually moved either to the outer boroughs or out of the city altogether as density (and property value) increased.

As these final remnants of chocolate manufacturing disappeared, there remained a decades-long void, bridging little gap between iconic brands of their day and the current crop of craft chocolate makers in the city. Once again, we find the number of New York-based chocolate makers fairly small (and admittedly, located primarily in Brooklyn).

Walking into the ICE Chocolate Lab each day, I feel honored to play a small role in the city’s rich chocolate history and as I wander the neighborhoods from the Financial District to SoHo to Chelsea to the East Village, I’m now constantly reminded of the names and places of chocolate-makers past.

Want to study with Chef Michael? Click here to learn about ICE's Pastry & Baking Arts program.