This ICE Instructor Used to Cook at the White House

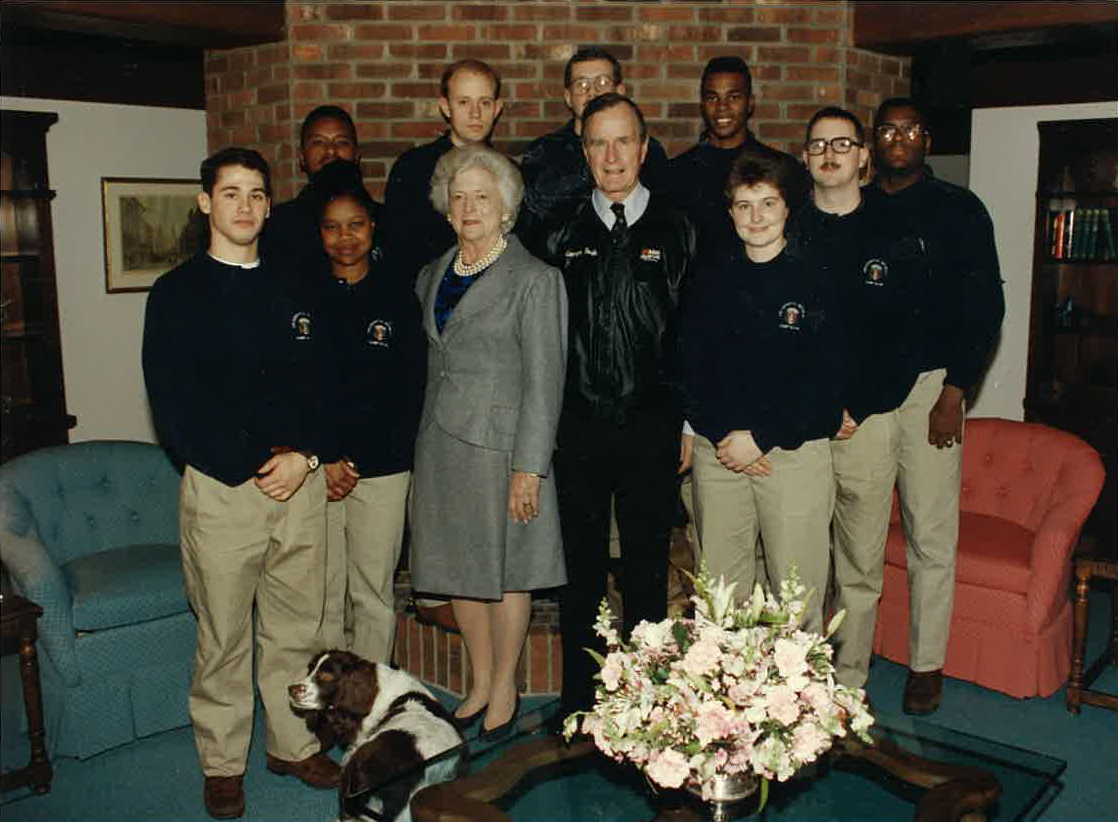

Lead Chef-Instructor Louis Eguaras cooked at Camp David and the White House from 1992 to 1996.

Los Angeles campus Lead Chef-Instructor Louis Eguaras knows first-hand what goes on inside the White House kitchen. Born in the Philippines, Eguaras first worked as a dishwasher and line cook at a tavern in Delaware at age 15. In 1991, he completed Navy boot camp, trained at the Naval Academy in culinary arts and was recruited to work at Camp David upon graduation. He was one of just two recruits chosen from a pool of 249 candidates vying for the prestigious post. From there, Eguaras joined the White House culinary staff where he cooked for celebrities, dignitaries and, of course, the first family. Chef Eguaras holds a fourth-degree black belt in Hawaiian Kenpo, and while that didn’t factor into his security clearance to work in the White House, he assures us that U.S. presidents are in good hands when it comes to the safety of their food.

There’s been a lot of talk about food at the White House. Inquiring minds want to know: how secure is the food preparation for a sitting president?

Security is pretty tight. Wherever we went, Secret Service went.

When the president travels, there is an advance team. I was part of [the team] in 1995 that traveled with the Clintons to Italy, France and Germany. Wherever the president was going, we would talk to the chefs and discuss the plan and deal with the kitchen. We would take a look at the pantry where everything was stored and make sure things like rat poison were not stored next to flour. Then we’d let the chefs know we needed to watch what they were doing and that we were going to jump in to plate for the president or switch things around. Many times I’d inform Secret Service that everything was secure.

Sounds like a serious responsibility.

It was. After we secured a location we were off until the president arrived. We’d take a few days to go through the itinerary and check out where he was eating, whether at a hotel or restaurant, and inspect the kitchens.

So when it comes to mealtime, should President Trump have cause for concern?

I don’t think President Trump should be worried. There’s a reason why they have the Navy [overseeing culinary] because if anything happens, you can be prosecuted by the Uniform Code of Military Justice and civilian laws. That’s why they screen everyone who’s going into the White House or Camp David to get top-secret clearance.

How did you wind up in the military?

My dad was in the Marines. He explained to me there are different branches of the military and that I should check them out, so I did. Anything food and food security is run by the Navy. My dream job was to be on an aircraft carrier and cook for 3,000 people. I chose the Navy because I heard they had a great culinary program.

Explain the process. How does one get to choose “culinary”?

Back then they called it Mess Management Specialist (“mess” means kitchen in Navy terms). After boot camp in Orlando they sent me to culinary school, for “A school”, at the naval training school in San Diego. After that, they send you wherever you want to go. I had lined up aircraft carriers in Rota, Spain; Signella, Italy; or Yakuska, Japan.

But, you didn’t wind up in any of those countries.

When I was two weeks into culinary school in San Diego, three recruiters came from Camp David in Maryland looking for cooks and young chefs to join the team.

I imagine it’s a pretty coveted spot. How did you get chosen?

I went for first, second and third-round interviews. A lot of people have told me about my attitude and how I deal with situations and problems. Master Chief Ron Ford said I was the most positive person — always smiling, always in a good mood — which I’ve always been. Eventually, myself and one other guy from Tennessee were selected out of 249 interviewees — just the two of us.

What was the vetting process like?

I already completed culinary school, but they sent me twice because I was waiting for my clearance. They sent me to “C school,” which is reserved for those who have been in the Navy for more than 10 years. During that time, I went through psychological testing, health exams and they talked to all my contacts in the Navy — superiors, colleagues — and my neighbors in Wilmington. They even spoke with Chef Charlie at Stanley’s [from my first dishwashing job].

They must’ve recognized your potential to send you up to C school.

They were going to send me to work in an office, but Master Chief Ron said, “That’s a waste of his talent. I want to send him to pastry arts, cake decorating and Flag Duty.”

What’s Flag Duty?

Flag Duty is where you learn how to act when working for admirals and above. Similar to a management training program, but it’s learning how to work for dignitaries. Eventually I’m going to say, Mr. President, is there anything else I can get you?, Can I make you something?, Can I get you some coffee?, without being nervous.

Do you feel that particular training effects how you currently operate?

Yes. A lot of the training I received was based on military training and how to deal with high-echelon guests. I really honed [the skill of] being professional at all times. Whenever you’re doing catering you have to stand a certain way, be away from the line of sight so you’re there but you’re not there — a fly on the wall. There’s a lot of technique to how to act so you’re not seen. You’re constantly watching what the president needs — I’d be looking to see how much water is on the podium and on the table. You pretty much go in and get out — don’t make [a] scene, don’t linger, don’t do hand gestures.

How often were you in contact with the president?

Bush, Sr. [George H.W. Bush] was there every weekend. I worked in Laurel and Aspen. Aspen is the main cabin of the president, the residence where the president and family stay and relax. Laurel is where the president does his meetings, like the Camp David summit. It seated 16 people in the conference room and the office is where the president can function as he does in the Oval Office. It has a nice lanai, grill area and fireplace.

What was your day-to-day?

If the president was there I’d be taking care of breakfast, lunch and dinner and a small amount of catering — like creating platters. We were also in charge of other cabins — Maple, Sycamore, Poplar, Oak — that’s where the president’s guests stayed. I took care of Demi Moore and Bruce Willis, George Strait, Amy Grant, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Prime Minister John Major [from Britain] and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney from Canada. We did a lot of guest relations. I went to town, which literally has one traffic light, to pick up toiletries for Demi Moore once.

Was it a formal environment?

As the Bushes didn’t like using Navy terms, we were called by our first names. They were very personal. Barbara wanted to be called Mrs. Bush and would say, “Hey Louis, what do [you] have for breakfast? Steak, bacon, toast, eggs?” Mr. Bush would say. “Give me a few sunny side up eggs. I’m trying to watch my figure! And a few slices of bacon.” I’d come in early to brew coffee, get country-style potatoes started and then eggs and what not, got water ready in the morning for oatmeal. It really got me into the practice of being a private chef.

You went from Camp David to the White House. What was that transition like?

Everything was much more formal.

After Clinton won the election, he didn’t go up to Camp David as much and the Navy started to downsize. An opportunity came for me to go to the White House, so I put in my request. Within two weeks I was at the White House. I’m so thankful for it. I don’t take anything for granted.

You must have cooked for some pretty incredible people.

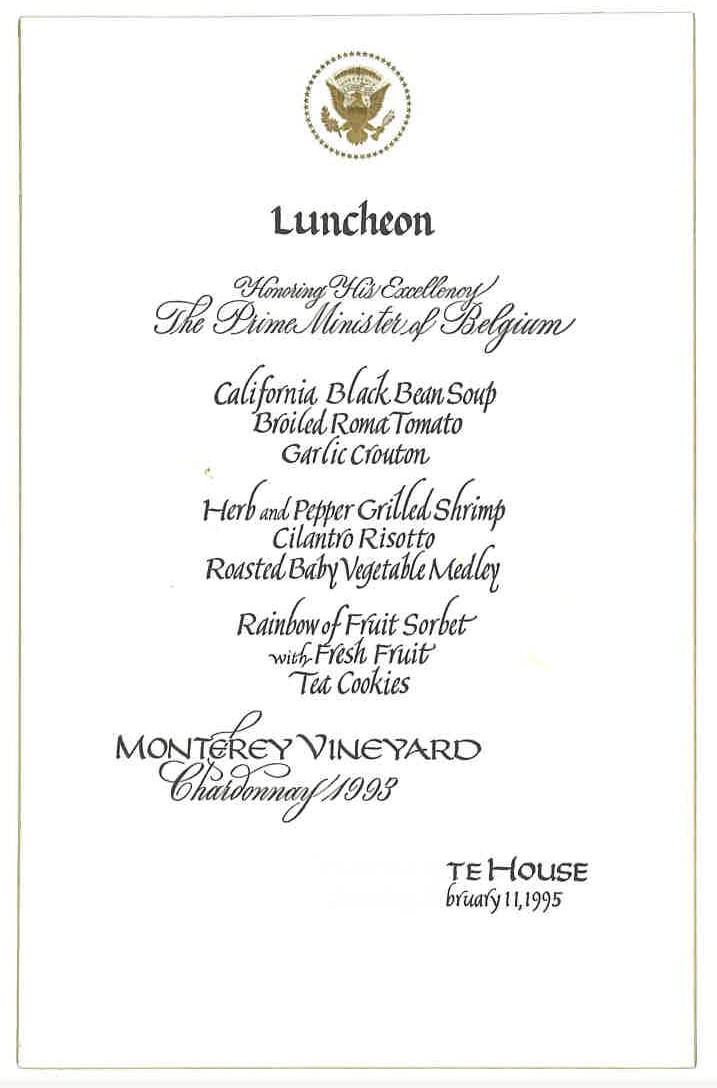

We worked a lot of dignitary events and state dinners — Japan, Canada, but my most memorable one was when Nelson Mandela was released from prison. We had a huge dinner to welcome him and I got to shake his hand.

How did you wind up teaching at ICE?

One day I started teaching my wife, Agnes, how to cook. She told me I should teach culinary arts as she really liked the way I taught her. When I worked at the White House and Camp David, and even the French Embassy, I had really great chefs who taught me a lot and were great mentors to me. I decided to get into teaching because I want to share with students my experience as a chef and possibly mentor students into a similar direction.

I came to ICE because I loved everyone that was already working here. I have worked with these chefs in the past and have kept in touch with everyone throughout the years. I also already knew about ICE in New York, so opening ICE Los Angeles was very exciting to me and I wanted to be a part of it.

How is your experience in the White House informing your teaching now?

I always tell students if an opportunity presents itself — take it. The opportunity that came up with Camp David led to the opportunity to work at the White House. I never turned down any offer that came my way. That’s my philosophy. Whatever door opens up, take it and enjoy the ride.

The other part is attitude. Those are two things that I tell students, because when you go somewhere you never know where it’s going to lead. You have to keep a positive attitude — I got recruited because of my attitude. Whether at the Ritz or Intercontinental Hotel or at the White House, people want to be around positive people.

You can meet Chef Eguaras in person on a tour of our Los Angeles campus. Plus, see how a former military sergeant found his way to instructing pastry and baking at our New York campus.

He is one in a million Chef..

Submitted by Humphrey on August 1, 2018 11:05pm

I have been taught by Chef Eguaras and I am glad to have met him..He is one of the best Chef Instructor I have ever come accross...He is very dedicated, passionate, and makes sure the students are as successful as him...Much love Chef Eguaras..You told me a lot of life values...

Add new comment