In today’s food culture, ingredient-focused or “farm-to-table” cuisine has become so commonplace that many young chefs can’t remember a time before it existed. Before the dawn of Instagram, food blogs and YouTube videos, a generation of chefs willed this movement into existence through a series of earth-shattering cookbooks.

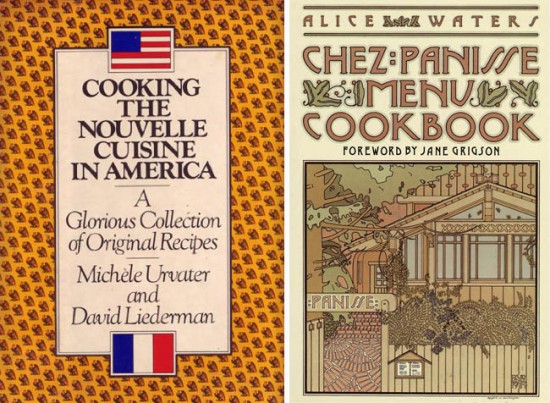

Those books — most importantly, "Cooking the Nouvelle Cuisine in America" and the "Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook" — reshaped the culinary landscape and have since paved the way for such famous chefs as Thomas Keller and Mark Ladner.

In the late 1960s, the nouvelle cuisine revolution shook French cuisine and culture to its core. As more and more Americans began to travel abroad after the war, it was inevitable that this movement — characterized by fresh ingredient-focused cooking and artistic presentation — would have a profound impact on modern American cuisine.

The result was an equally innovative shift on American soil: a regional cooking revolution that began with what the media dubbed "California cuisine." In 1979, two young American cooks, Michèle Urvater and David Liederman, published a text called "Cooking the Nouvelle Cuisine in America". This book was one of the first cookbooks available in the U.S. that comprehensively explained the principles and techniques of nouvelle cuisine and made them accessible to American cooks.

As a young chef, I had more than one epiphany while reading this book, and today my copy is quite dog-eared after many re-readings. In "Cooking the Nouvelle Cuisine," Urvater and Liederman spoke eloquently about how the culinary principles codified by such French chefs as Ferdinand Point had turned the classical cuisine of Escoffier and Carême on its proverbial head.

In short, Point realized that, after the war, the old school style of cooking no longer fit into the lifestyle of contemporary French people. He preached that chefs should be more creative with their menus and that their dishes should reflect what was immediately available in the marketplace. Within the guidelines of nouvelle cuisine, menus also became smaller and more manageable, reflecting the need to change with the seasons and the ability to work with smaller kitchen "brigades."

From a technical perspective, Point preached eliminating starch thickeners from sauces. Instead, chefs could create sauces of a much lighter quality based on a series of reductions (a technique called "stratification" based on the work of Andre Guillot). To complement this change, Point recommended that chefs emphasize lighter and quicker cooking techniques such as sautéing, steaming and poaching. He recommended simpler plated presentations to highlight the natural integrity of the ingredients. If you’ve eaten at an upscale restaurant in New York City recently, you’ll have seen all of these principles in action.

A few years later, a second nouvelle cuisine-minded text furthered this movement: the "Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook" by Alice Waters. I could write a whole doctoral thesis on the significance of Waters’ impact on the history of American cooking. Together with other leaders of the California cuisine movement, Waters radically altered the manner in which culinary professionals produce, grow, prepare and present food — both on the plate and on a menu.

In addition to the principles of nouvelle cuisine, Waters was profoundly influenced by the ancient principles of Japanese cooking. Benefitting from the abundance of agricultural resources in California, the staff at Chez Panisse captured the imagination of a whole generation of American cooks and chefs. What the Declaration of Independence was to colonial Americans in the 1700s, the introductory chapter of the "Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook" was to 1980s American chefs.

Called “What I Believe About Cooking,” it was truly a culinary "shot heard 'round the world." Waters explained how alienated and alienating our experience with food and cooking had become since World War II. In particular, Waters’ greatest contribution was in the idea that, “No cook, however creative and capable, can produce a dish of a quality any higher than that of the raw ingredients.”

I was lucky enough to work under Waters at Chez Panisse. One of my most endearing food memories includes the first time that I smelled fresh, earthy, piney chanterelle mushrooms from the Pacific Northwest. Or when I tasted Waters’ famous baked goat cheese salad with baby lettuces that were locally grown in the Berkeley Hills. Each week, the kitchen staff would anxiously await the printing of the next week’s menu — a so-called "gazetteer" that featured small, local producers.

Other chefs may name other books as the ones that defined their careers, but for the students who ask about my formation as a cook, I always recommend they read these two texts. While it’s important to stay up-to-date on modern trends in food, learning about the roots of contemporary American cooking can both further young chefs’ understanding of current kitchen culture and spark their personal creativity.

Further reading:

- "Modern French Cooking for the American Kitchen," Wolfgang Puck

- "New American Classics," Jeremiah Tower

- "California Dish," Jeremiah Tower

Wish you could study with Chef Ted? Click here to learn more about our Culinary Arts program.