Earlier this month I had the honor of cooking for an American icon: chef and author Jeremiah Tower. The dinner was part of the second annual Imbibe & Inspire conference in Chicago, the broad theme of which was “The Roots of American Food.” Jeremiah was the guest of honor, celebrated as a luminary who refined and redefined our understanding of American regional cooking during his groundbreaking tenure at Berkeley's Chez Panisse in the 1970s.

By rejecting any product he considered inferior and focusing on the idea of local (which was surprisingly difficult in those early days), Jeremiah's efforts made possible the farm-to-table relationships that are so prevalent today. In the 80s and 90s, with his Bay Area restaurants Santa Fe Grill and Stars, Jeremiah set in motion many ideas which were ahead of their time, both in the front- and back-of-house. His efforts helped evolve the cultural status of chefs back when the food “scene” we know today was still in its infancy.

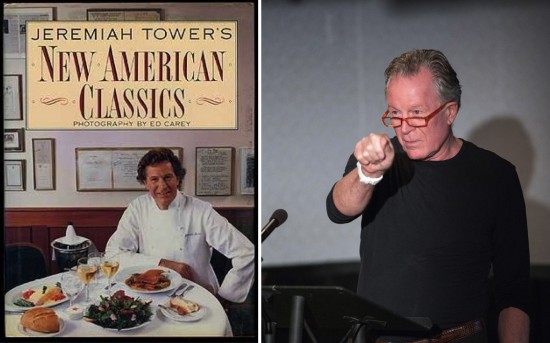

Seeking inspiration for the dinner at Chicago’s two Michelin star L2O, I returned to Jeremiah’s important (and, sadly, out-of-print) first cookbook, New American Classics, published in 1986 (thanks to the lone copy held in the archives at Kitchen Arts and Letters). It was the books of this era that comprised my own stitched-together culinary education, and revisiting this one made me realize just how fresh Jeremiah’s perspective remains today.

Through Jeremiah and his contemporaries, I began to discover the underlying stories connected to food and cooking, the sense of place that heightens our appreciation of ingredients. Jeremiah often relates the frustrating hardship in finding things as simple as fresh herbs and olive oil back in the 1970s—staples that we take for granted today. Just as we now can’t imagine the world without the Internet, it is increasingly difficult to imagine contemporary cooking without the bounty of high quality ingredients we either ship in from overseas or forage in nearby fields.

The concept of “quality” is key. Though we have a tendency to shift focus toward the technical and manipulative fanfare of cooking, Jeremiah’s work reminds us to respect those products that are special enough to be left alone (their discovery and acquisition were a revelation in the first place).

His guiding philosophy of identifying “benchmarks” is also an important lesson for young cooks: until one has tasted the very best products— whether apples or oysters or Champagne—how can one know whether any particular product is either good or bad? The same is true of complete dishes themselves; Jeremiah has always encouraged travel as a means to experience the benchmarks for specific dishes and the flavors of the places where they originate.

For example, while in Chicago, he recalled the story of the time he flew one of his chefs to France—just for the weekend—in order to cook and taste the legendary blue-footed Bresse chickens from the region of Burgundy and the Rhône valley.

Whether talking about the evolution of plated desserts, or attempting to trace the roots of “modernist” technique, I increasingly find myself referencing the French nouvelle cuisine movement of the 60s and 70s, when young chefs leaned toward lighter preparations, seasonality, a sense of place, and a creative break with the staid classics of the past.

While at Chez Panisse, Jeremiah was among the very first chefs to express those ideas on American soil, with the seminal Northern California Regional Dinner in October 1976 (Tower says of that night, “That was the spark that lighted the revolution”).

As much as Jeremiah helped propel the ideas that we now recognize as “California cuisine,” he also provided the necessary push for chefs everywhere to explore the flavors of their own regions. Anthony Bourdain, who is currently developing a documentary about Jeremiah, says, “He was the original. He was the first chef in America that you wanted to see in the dining room. He was the guy who transformed American menus from what they were to what they are now.”

The L20 dinner honoring Jeremiah was the culmination of two days of talks and tastings organized by Stephen Torres. Two of my desserts capped a multi-course menu from Dominique Crenn (San Francisco), Bryce Shuman (NYC), Erik Anderson (Minneapolis), Kyle and Katina Connaughton (Sonoma), Kevin Farley (Berkeley), and host chef Matthew Kirkley (Chicago).

Dinners like this are my favorite events to participate in; the convivial atmosphere of the bustling kitchen—seeing old friends and meeting new ones—was made all the more special with the appearance of Jeremiah himself. It’s an incredible feeling as a cook when someone who has been a longtime hero becomes a peer and friend.

Chefs today wear many hats—cook, business owner, media expert, and mentor. My brief weekend in the shadow cast by Jeremiah Tower’s influence reminded me that one of the contemporary chef’s most important roles is that of historian.

As much as we are bound up in the present, we must place what we see today in the context of the entirety of culinary history, and it’s critical that we pass that knowledge on to the next generation of young cooks. The more we blaze new trails into the future, the more we recognize that we cook on the shoulders of giants who paved the way before us.

Curious to learn more about other influential chefs and culinary professionals? Don't miss Michael's reading list for aspiring chefs.