If I were to ask you to describe the physical characteristics of chocolate, chances are you might think of a dark, shiny and brittle bar that slowly melts in the mouth. Perhaps you might immediately associate its rich flavor baked into a brownie or concealed within a creamy bonbon. You wouldn’t be wrong, of course, as chocolate has found its way into countless applications — a sweet shape shifter that pairs perfectly with our favorite flavors. That hasn’t always been the case.

For much of its history, chocolate wasn’t something we would eat out of hand or find in a dessert recipe.

The modern chocolate bar didn’t emerge until the mid-1800s, when technology and inventiveness converged. When Casparus van Houten developed the cocoa butter press in the 1820s, he was originally after the pressed solids — the cocoa butter (the fat that makes up over 50 percent of a cocoa bean) was merely a by-product. It would be many years before a chocolate maker (most likely the Fry family in England) would come up with the idea to add some of that extra cocoa butter back into ground cocoa beans and sugar.

At this point, chocolate began to resemble what we think of today, and its texture and flavor would evolve further as the industrial revolution continued in the decades to follow. Before that breakthrough? When one mentioned chocolate, they were really referring to a beverage. We can trace the history of chocolate back thousands of years to the Olmec, Mayan and Aztec cultures of present-day Mexico and Central America.

These early chocolate makers cultivated the cacao tree, ultimately rendering the seeds of its fruit (the bean) into a drink. What these cultures enjoyed, however, bore little resemblance to a package of Swiss Miss. For starters, it wasn’t served hot, and most likely unsweetened, rather made with water and flavored with spices and flowers, then made frothy by repeatedly pouring from one vessel into another.

The beans themselves were of great value and a significant staple crop, though most historians suggest that it was only enjoyed by a few, and not necessarily a part of the average person’s diet, rather used primarily for medicinal and ceremonial uses. Most culinary applications — even savory mole — appeared much later. After the Spanish conquered the birthplace of chocolate in the 1500s, it would undergo further changes as it made its way to European drinkers.

The first to adapt the Aztec beverage were likely the missionaries tasked with “converting” the indigenous people. By the time chocolate took hold back in Spain, it would evolve into something recognizable today — served warm, sweetened and whipped to a froth using a wooden molinillo. It remained, however, a treat for nobility, as it slowly spread throughout Europe.

This growing taste for chocolate, which would become a beverage on par with tea or coffee, also led to its cultivation in European colonies in tropical zones throughout the world. For two centuries, its popularity surged but remained something not to eat, but to drink.

When van Houten sought to remove cocoa butter from the preparation, his goal was to make a lighter beverage, with much of its fat removed — what many at the time referred to as digestible cocoa. Soon after, digestible cocoa became increasingly accessible to a wider audience, taken in the morning or in the afternoon as a pick-me-up.

Chocolate would also be touted for various health benefits and considered a gentler alternative to its cousin, coffee. As chocolate culture progressed, it did of course find its way into bar form (and then confections and baked goods) in the mid-1800s. By the turn of the 20th century, cocoa and chocolate were firmly embedded into our daily regimen.

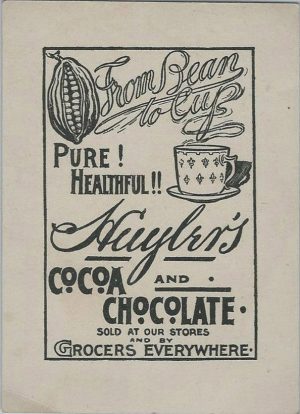

My own research into chocolate history has led to some interesting discoveries: colorful Victorian-era cocoa tins decorated with imagery of cacao pods, and even references to “bean-to-cup,” foreshadowing the “bean-to-bar” term we now use more than a hundred years later. All of this research of chocolate’s history has renewed my own interest in its drinkable form. I’ve been studying both ancient recipes and more familiar adaptations.

As the weather turns, I can’t think of a better way to warm up than with a frothy cup of hot chocolate, while quietly considering the complex journey this magical bean has made over the centuries. Below, my favorite modern recipe, inspired by Mexican-style chocolate prepared today, is deep in chocolate flavor with subtle accents of unrefined sugar, warm spices and a touch of heat from dried smoked chile.

Ingredients

- 1 quart (950 grams) whole milk

- 1/4 cup (60 grams) heavy cream

- 1 cup (200 grams) grated panela, piloncillo, or light brown sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon (2 grams) salt

- 2 sticks whole cinnamon

- 2 pieces whole star anise

- 1/2 teaspoon (2 grams) powdered chipotle morita (or to taste)

- 1 vanilla bean, split and scraped

- 7 ounces (200 grams) dark chocolate, roughly chopped

Directions

- Combine the milk, cream, sugar, salt, spices, and the vanilla bean in a medium saucepan and bring to a boil over medium heat. Reduce heat to low and hold at a bare simmer, stirring occasionally, for five minutes.

- Whisk in the chopped chocolate and continue to simmer an additional five minutes. Remove the vanilla bean and the whole spices. Blend well with an immersion blender to create a froth and serve immediately.

Experience the chocolate lab in ICE's Pastry & Baking Arts program.