Chefs You Should Know

The French Chef Who Changed American Cuisine

As a young cook honing my skills in the mid-1990s, I fell into a position at Emily’s, a small restaurant in suburban Detroit led by Chef Rick Halberg. With twenty years’ hindsight, I now look back at my time there as an important educational phase of my career — a cook’s equivalent to graduate school. The food culture we see today was only in its infancy then, and our resources were limited to print — this was well before we could scan social media feeds for instant inspiration and ideas from around the world.

Emily’s served as a creative incubator for the cooks who worked there. In our downtime, we swapped the latest books and magazines, mining them for techniques and flavors to infuse into the menus we developed. We looked to Europe, of course, but we were also keenly aware of the rumblings here in the U.S. Then, as now, it was an exciting time to be a cook.

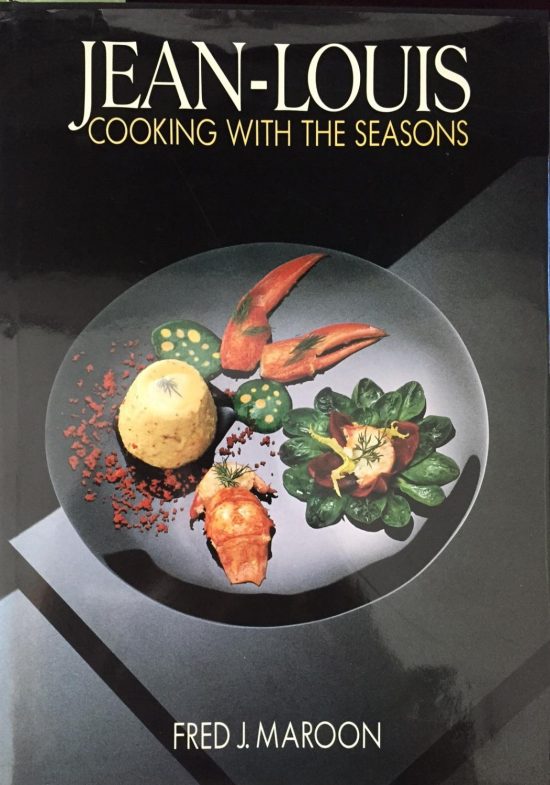

Our research materials included dog-eared copies of Art Culinaire (still publishing and quite relevant today), rare issues of the European import Opt Art and the highly influential series of books Charlie Trotter began writing in 1994. One book, however, stood out among the pack: Jean-Louis Palladin’s Cooking with the Seasons, originally published in 1989. By day we cooked French-inspired classics, but at night we studied Jean-Louis’ modern and sophisticated interpretations, documented in sleek photography.

Though highly refined techniques and luxury ingredients jumped from every page, the book also served as a love letter to the ethos of “local” and “seasonal” cooking. I recall one dish that we ended up adapting into our repertoire: a deceivingly simple but elegant terrine fashioned from ultra-thin slices of house-cured salmon, spinach and anchovy butter. As my own path was heading toward a concentration in pastry, I also experimented with the book’s dessert recipes, including Palladin’s traditional clafoutis (a staple of his native southwestern region of France) and a raspberry-studded crème brûlée.

Though perhaps eclipsed by chefs who came after (and those who became more ‘famous’), Jean-Louis’ influence on American cuisine can’t be overstated. He was often considered a “chef’s chef.” Cooking styles and aesthetics have changed and few are replicating his dishes today, but his legacy lives on with respect to his insistence on local ingredients.

One might argue that most French chefs in the U.S. in the 1970s and 1980s relied on imported ingredients. Palladin, upon arriving in 1979, made it his mission to seek out the best of what was here. His flagship restaurant in the storied Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. showcased these products with impeccable technique to honor them.

A compatriot in this cause was Gilbert LeCoze, who opened Le Bernardin in New York; rather than ship Dover sole from Europe, LeCoze walked the stalls of Fulton Fish Market and championed fish from this region’s waters, and in the process changed the way American chefs sourced and cooked fish. And by no coincidence, Eric Ripert, the current chef and owner of Le Bernardin, worked under Palladin when he emigrated from France, just prior to being hired by LeCoze.

I was afforded my own personal introduction to Jean-Louis years later in 1999, when he cooked as a guest chef at Tribute (also in Detroit), where I had recently become the pastry chef. Many lasting impressions came of these guest chef dinners over the years, but few memories top observing Palladin’s confident swagger at the stoves, his missives barked in an impossibly deep voice and thick French accent. Sadly, Jean-Louis would pass away two years later at the young age of 55, still very much in his prime.

But since then, I occasionally pull his book from the shelf and contemplate the evolution of cuisine — what has changed and what fundamental ideas remain the same. I will also quiz younger cooks from time to time, to test their knowledge on the influencers who came before us — I can count how many cooks I’ve sent to the internet in search of Jean-Louis and his generation of chefs.

I was offered an opportunity to come, in a sense, full circle within my own Jean-Louis story, and straight into his old kitchen at the Watergate just last month. At the urging of my friend Paul Liebrandt, I accepted an invitation from current Watergate chef Michael Santoro to celebrate Palladin’s legacy and the 50th anniversary of the Watergate Hotel. An exclusive multicourse dinner also featured D.C. chefs Robert Wiedmaier, Brian McBride and Watergate pastry chef, Kieu-Linh Nguyen. The most difficult decision was which dessert to prepare, but after several days’ deliberation, all I needed to do was flip through Cooking with the Seasons and the inspiration became immediately clear.

Upon seeing my old friend — that raspberry crème brûlée — I created a dessert that served as a metaphor for my own evolution: a sphere of vanilla mousse hiding a liquid raspberry center, glazed with raspberry and set upon a shortbread base. Inspired by the original, this dessert represented a culmination of skills acquired in twenty years, yet still clean and deceptively simple — in the manner of how Jean-Louis taught us to cook.

It’s your turn to study pastry arts with the masters — click here for more information on ICE’s Pastry & Baking Arts program.

Add new comment