Borrowing Lessons from Architecture in the Pastry Kitchen

In the past, I’ve written about the parallels between architecture and pastry. I recently judged a competition where architects were asked to express their favorite iconic buildings in the form of cake. Once again, the topic of architecture and pastry arts came to mind.

I think a lot about architecture and design. It's a closet interest of mine, though I must admit that my passion is limited to: I don't know much about architecture, but I know what I like. One of the benefits of urban living is being surrounded by so much of it. I'm fascinated by the juxtaposition of various styles, shapes and sizes — sometimes even more than the individual structures themselves.

While the streets of Manhattan may be more chaotic than, say, the carefully planned vistas of Paris, a glance down any street or avenue can be just as awe-inspiring. Without overreaching, there are some great analogies to be made between cooking and architecture. Both are seen as lofty arts and technical crafts. Both provide a vehicle for fashionable trends and practical function. Both reflect their immediate environment and in turn, give that place a sense of unique identity.

Occasionally, both incite controversy. As two of the three necessities of life, food and shelter hold the kind of sociological importance that can even spawn whole philosophies.

You may think you know where I'm headed with this: Toward a discussion of architectural foods such as the towering desserts of years past — but this is just the surface. Of course, presentation is an important factor in fine dining and these trends come and go.

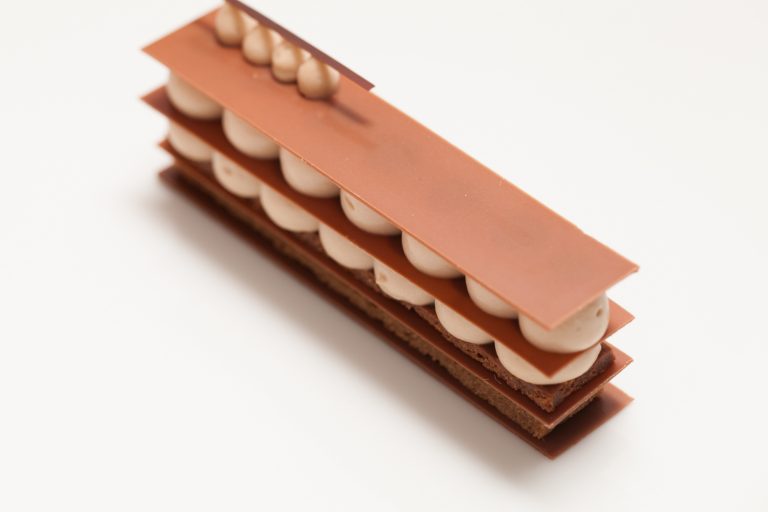

In fact, in recent times our food has slowly retreated to the surface of the plate, often appearing as if randomly scattered, sometimes even ignoring the conventional boundary of the rim. The true "architecture" of a dish, however, is less about looks or visual construction and more about the "architecture of taste"— how blending elements creates a visually appealing framework for flavor and texture.

Contemporary cooks take many factors into consideration – materials, technology, aesthetics and matters of perception. Modern cooking seems to be an intersection of engineering and philosophy. Years ago, I read about the construction of a project in Switzerland that perfectly reflected this discussion: The Blur Building, the goal of which was to create an indeterminate "structure" of water vapor.

On the same metaphysical level, a chef friend once pondered how to make food float in mid-air. It’s interesting and important for both disciplines to question themselves. Is a building without walls still a building? Was that dish I ate just dinner or something more?

That said, at the end of the day, food is just food. Though I pay way too much rent, I need a solid room in which to rest. As a sentient being, I ultimately seek comfort and pleasure from both. But as a chef, what concerns me is how the various elements of a dish — taste, texture and temperature — are engineered and arranged to provide the maximum impact.

We achieve this through complement (classic flavor pairings, as well as the unconventional) and contrast (sweet and tart, smooth and crunchy, hot and cold, etc.). One caveat I learned early on: No matter how well two or more elements might go together, each must also be able to stand alone. Attention is also given to the structure itself — the form of how we eat and experience a dish.

The thought process behind how diners will approach a plate of food mirrors how architects envision how a space will be navigated by its inhabitants. Cooking from an architectural perspective goes beyond creating a pleasant-looking dish. It helps us refine our approach by thoughtfully layering flavors and textures; using techniques to best express the qualities of our ingredients; considering how the consumer will ultimately experience our final product.

Though architecture and food serve practical purposes, constructing with an eye for maximizing experiential enjoyment elevates practical forms to a works of art.

Want to study Pastry Arts with Chef Michael? Click here to learn more about our career programs.

Add new comment